ALBERICO VERZOLETTO: THE MAN AND HIS ART

An artist with a vast and varied production, spanning from the ‘50s of the 19th century to the first decade of the 2000s, Alberico Verzoletto is a man with a multi-faceted personality. Fiery impulses, brooding melancholies, antithetical emotions giving rise to the chromatic contrasts seen in his works coexist in him. His frequent silence does not stem from a lack of arguments, rather from conscious, free choices: the canvases do the talking, the canvases speak to the most sensitive viewer directly and with great intensity. To call him one of the many “valley painters” would be a gross reduction; in fact, the complexity of his research, both personal and artistic, goes beyond any possible definition, beyond the geographical and cultural limitations of his formative environment and, still to this day, hasn’t been adequately valued and recognized. This is partly due to the freedom and solitude which inspired his life choices, but mostly to the moral coherence which basically made him immune to the flattery and pitfalls of the contemporary art market. Since childhood, he shows a lively interest for drawing, tirelessly filling small sketchbooks, as well as any reclaimed paper support such as disassembled cardboard boxes, blank book pages, and the back of posters, with numerous images in pencil and pen, drawn from real life or from pictures, illustrations, and comics, portraying a vast array of subjects. His youth is also characterized by the production of carved wooden sculptures, often made with reclaimed materials such as old broomsticks from which he creates surprisingly agile and detailed statuettes. His physical education, on the other hand, is left to a passionate practice of cycling, which he practiced on a professional level for some time.

In his younger years there are two significant encounters: his future wife Giancarla Mazza, and Alvaro Rossetti, painter and traveller that enthrals him with tales of a mythical Paris, inhabited by extraordinary, revolutionary artists, the pioneers of the modern movements. Verzoletto then carefully studies the impressionist painters, the post-impressionists, the French expressionists, in a constant effort to catch the technical innovations in their framing, their brushstroke, their chromaticism. Nonetheless, he is interested in the Italians from the 1900s, such as Carrà, Casorati, Morandi. He explores and widens his horizons, increasingly challenging himself with painting.

His path as been compared with the likes of Pissarro, de Vlaminck, Dufy, besides Van Gogh, Matisse, Cezanne, and moreover, with symbolist painters, primitivists, fauves, even metaphysical painters. However, one must acknowledge Verzoletto’s creative autonomy and technical proficiency, necessary conditions for his peculiar identity and a coherence that make him almost unique. His production is non-derivative, on the contrary it is extremely varied and multifaceted, characterized by a precise style which makes him recognizable at first glance and separates him from any other master of the paintbrush.

An important stylistic reference point for him is a painter from the previous generation, Ido Novello, which gives assistance to the young colleague at first, encouraging him to work not driven by improvisation and spontaneity, but rather focusing on strong intellectual motivations, finally lifting a screen between environment, society and himself.

He gets powerful visual stimuli from the lands that surround him, with which he feels a deep connection. Lands with a complex mountainous profile, with surprising chiaroscuro contrasts to be discovered little by little, and that he portrays with an expressive code that gets more and more peculiar. He can observe, but he can also interiorize and interpret, in what the critic Gian Piero Rabuffi calls “a real emotional permeation with the subjects”[1].

Painting has now become a real vocation for him, such an absolute one as to bring him to flee social occasions and get himself closer and closer to nature, favouring a relationship with the arboreal species rather than the human one. A gentle, yet resolute stance.

Visiting Verzoletto’s house, especially exploring its library, reveals many of his artistic and literary interests. He reads critical texts by Zeri, Panofsky, Vattimo, Marangoni. He owns the entire collection “The Masters of Colour” and a history of Italian painting from Futurism to the present day, besides many monographs on ancient and modern artists. He is interested in a deep examination of the mindset of painters he feels kinship with. It is not surprising, then, that he owns exquisite editions of the letters of Van Gogh, Gauguin, Modigliani, and others. He piles up his thoughts on reclaimed cardboard – “What is poetry? What is music? What is art? What remains after all else is gone”– or he transcribes quotations that touched him profoundly: “An artist has no obligation towards reality; he only has it towards his own vision” (Pietro Citati), “Landscape painting summarizes and contains everything: it is sacred painting, music, poetry” (Roberto Tassi). On the last one, penned just moments before his death and addressed to his wife, he simply writes: “I paint”.

A blunt summary of a whole life.

In the rare but enlightening interviews, he uses sentences that are sometimes intense and dramatic, sometimes witty: “For me, painting is a struggle and takes effort, but it’s a necessity: I have to do it because I can’t help myself”.

Being self-taught, he gets labelled as a “Sunday painter”, and to the journalist asking him in an article for the Eco di Biella in 1966, if he recognizes himself in the definition, he replies: “Personally, I never paint on Sundays. Preferably, I paint in the night hours, fighting with sleep. I told you that for me, painting is a liberation and a suffering at once. I think the definition is mainly referred to the artistic activity of people who also have another job in their life. For example, I work for the Zegna industry in Trivero, I’m a factory worker”. Moreover: “I always loved to scribble with a pencil, but the real sense for painting came around my twenties”. About combining the needs of painting and working, he declares: “I don’t think it’s a matter of combining, but rather of splitting oneself.

In the factory, one does a job that requires total commitment, so when I’m in the factory I never think about painting, my dedication is all practical and aimed towards those things I do in fixed hours. After that, I become someone else: outside of any commitment and obligation, I feel I can talk a language that is my own, independent from any bond that is not my personality. This way, painting completes my life, as a gift”. The interviewer then asks if the amateur painting of the workers must be considered a distraction, receiving the following answer: “I already told you that for me, painting is something really serious, as any manifestation of thought; if I were looking for a distraction, I wouldn’t do so through artistic expression, since it’s deeply engaging”.

About how he gets the idea for a painting, he says: “Something I’ve seen, a sound, a talk with a friend, the words turn into pictorial images I then elaborate on…all the things in life interest me, in each one I find a reason to observe. My work is done mainly indoors and in complete silence. I’m cautious, as any good Biellan. I’m an amateur, and I have to keep it to that. To be, one day, just a painter, is a dream: what matters now is to be able to do good, clean things[2]”.

On another occasion, he speaks about his workflow: “Art, for me, is a terribly hard thing. Even if I think I’ve reached a certain level, I realize I have much more to learn. This brings destructive fury on my works; I often do it and then I feel better, because in doing it I see an improvement, another step forward in my paintings”. His sharp humour comes out in this joke, short yet trenchant: “Life…at first, I’d say: what a rip-off. But then, since we’re here, it’s worthwhile living”.

In a 1962 interview, when asked for his opinion on artistic education in schools, he replies: “We should teach what is beautiful in every scholastic curriculum. In general, curriculums only teach what is useful and necessary, forgetting that the human personality also needs to develop artistic sense. This sense would greatly help with the education of youth, it would increase their sensibility and increase the development of that part of personality which often finds no outlet, suffocated, as it is today, by technicism”.

Over the years, other places attract his attention, beside Piedmont: Liguria, Tuscany, Umbria, Sardinia. Verzoletto himself describes his creative workflow in the discussions with his rare friends: initially, he goes out to work en plein air, but what he gets from this is a mere compositional and chromatic suggestion, a sketch that is then reworked in the studio. Objective naturalistic data, exteriors, and subjective, interior sensations stratify on his canvases, offering surprising interactions.

In his maturity, he prefers artificial light to natural one, or more precisely, he leaves behind the exteriors to isolate himself in the comforting seclusion of his studio, where he can sound out the depth of what lies beyond the visible form.

The urgency and passion with which he frantically works to hundreds of different pieces remains unchanged, increasing instead. Painting, by his own admission, helps him better the quality of his life, physically and spiritually. After looking inside and out of him, he gains awareness of the principles of unity and multiplicity, also via the practice of Eastern meditation techniques, which is to say that the individual is the result of the opposition the All that they’re part of, getting energy from the universe and releasing it in an endless cycle.

He shares a spiritualistic view of art with his wife and some of their friends. Giancarla, talking about her husband’s painting, quotes the words of the Bulgarian philosopher Omraam Mikhaël Aïvanhov: “The true artist achieves the true synthesis of philosophy, science and religion, because being an artist means actualizing what intelligence conceptualizes as right and true, and what the heart feels as good, so that the superior world, the world of the spirit, can descend and manifest itself into matter. The artist, in the ritual sense of the word, is he who has put order and reason in his thoughts and has been able to introduce love and peace in them. Then, everything he realizes is balanced and meaningful[3]”.

He establishes a particularly stimulating artistic relationship that lasts many years with the composer and guitarist Angelo Gilardino, whom he met during the “Guitar Vacations” in Trivero, an international summer school for guitarists opened in the 70’s, offering musicians with different backgrounds the chance for exciting artistic exchange with the artist. Gilardino compares Verzoletto’s work to a “secret fable” and says the painter is “tempted by myth”, describing with such evocative words the expressive-psychologic rather than descriptive use of graphical composition, colour, lights and shadows.

The two artistic languages–painting and music–are strictly linked.

A painter and a musician go along pretty well, given the two expressive forms even share their terminology: colour, tone, rhythm, composition, harmony, contrast, are just some of the base elements of visual and auditory messages, through which they conjure situations and describe situations.

Gilardino writes interesting critical texts to complement the painter works. Furthermore, he and his disciples play during the vernissages for his exhibitions. In exchange, Verzoletto offers his paintings as illustrations for Gilardino’s sheet music books and musical albums. During the “Naturalmente”[4] (Naturally) exhibition–an adverb chosen by the painter himself to define the peculiar exposition approach–the musician wonders about the meaning of the title, asking himself whether Verzoletto’s painting is natural or naturalistic, getting to the conclusion that it actually is a poetic operation starting from subjects that have more or less nothing natural, since they’re deeply anthropic.

He calls his painting “a poetic tale in images, turning places into creatures animated by a secret life”. Not even his technique is natural; Verzoletto, in fact, has created a “chromatic vocabulary” from scratch, obeying to his own rules and whims. Finally, the composer mentions the “figural architecture” of the painter “who is not afraid to subvert the rules of perspective and the projection of shadows” and that, once again, doesn’t have anything natural. What is really “natural” in Verzoletto’s painting is the mental process that defines him, through which he catches subjects from ordinary reality and transfers them into a fairy tale dimension, mythical and dreamy.

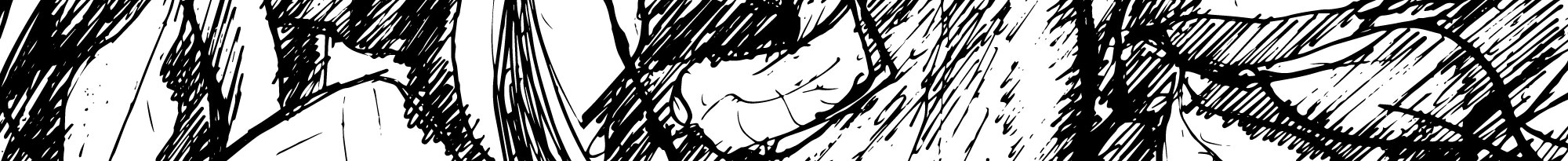

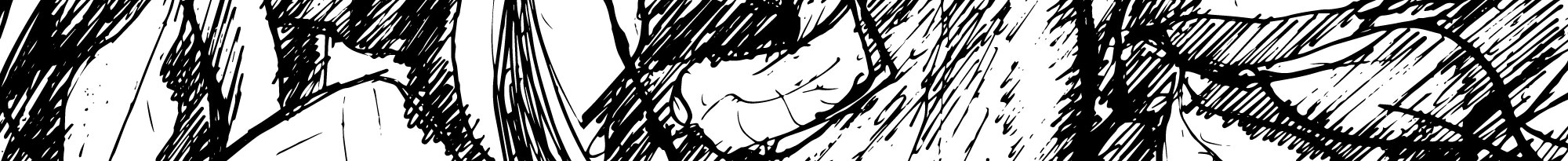

Talking about the pictorial matter, when watching the canvases closely and with oblique lighting, one can sense the painter’s gesture in creating them, mixing great quantities of colour with spatulas and using big, wide, flat brushes with hard bristles. Sign stems from gesture, and the definition of the background layers and the volumes comes from the movement of the sign. What is really surprising is the sense of tridimensionality of these paintings, the energy emanating from matter that fascinates the watcher, pushing them to an approach that is not just visual, but also tactile. Brushing the painted surface, running a finger across the grooves between brushstrokes, helps establishing true contact and a deep connection with the artist.

Pictorial matter is applied to the canvas in ways that change over the years: in the juvenile phase, with small dashing touches, with chromatic harmonies sometimes delicate and serene, sometimes contemplative and melancholic, as if they were pieces of a mosaic. Later, stretched out, ample backgrounds introduce boreal harmonies or vibrant and daring contrasts based on, but not limited to antinomy between light and dark, coldness and warmth, revealing a clear vision, mindful of details as well as the general picture. In other cases, the brushstrokes stretch in a marked hatching, in an increasingly directed flow, achieving a lavish and silky chromatic weave, with a texture as rich as a tapestry.

In his adulthood, the brushstrokes grow thick, dark or bright, and they curve, bend, encompassing figures and creating stark contrasts–of pure colors, chiaroscuro, as well as quality, quantity, synchronicity–leading to a radical turn towards vitalism, tinged with spirituality and mysticism.